Skip to content

The Davis Family Left an Indelible Imprint on the Case-Dvoor Farmstead

Part 1

By valuing our historical legacy, we honor those who came before us. We travel about Hunterdon County with a deeper understanding of this special place we call home. Their stories remind us of the challenges they confronted and overcame, and help instill in us the fortitude to do the same.

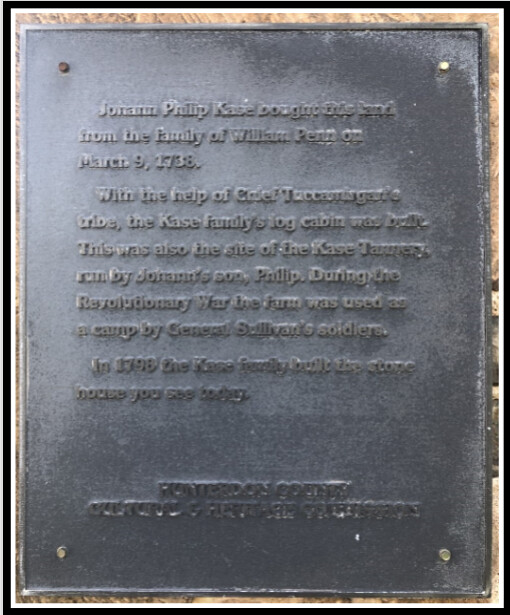

The historic Case-Dvoor Farmstead gets its name from two well-known families that lived on the property for many years. We have copious records of the Case family, who were among the early European settlers to this area and first farmed the property and built the historic farmhouse. And many people are familiar with the Dvoor family, who owned the farm for about 80 years, starting in 1920.

But there was a third family, the Davises, who also owned the farm for decades. While the Davises left an indelible imprint on the farm during their residence — from 1870 to 1910 — they left behind few records, and little was known about them. What follows is an effort to change that.

One wonders if Sandown, New Hampshire was a place where people preferred piety and precision — but were practical enough not to get too caught up in such matters. When Otis B. Davis was born on March 21, 1830, Sandown’s best-known feature was its meeting house, built in 1773. When planning its construction, a surveyor was directed to find the exact center of town. He did, but it fell right in the middle of a swampy meadow. The local deacons consulted each other, and “moved” the center of town to a nearby hilltop, which is where the meeting house stands to this day.

We know little of Otis’s youth, but can presume he loved to travel. Early on, he left Sandown and found work as a salesman with the Fairbanks Scales Company, driving about New England in a horse carriage.

—-

During one of his trips to Massachusetts, he met Elizabeth Davis; they married on Nov. 29, 1855, and their union lasted 62 years. Otis’s feelings for “his Lizzie” decades later were “still as young as upon their wedding day,” as recorded in the Brooklyn Eagle in 1915.

Otis and Lizzie moved to New York City, where their son, Charles, was born in 1857. Otis is listed as working in “scales,” in the 1857-1859 NYC Directory. Then, the story gets a little murky.

Otis disappears from the 1860 directory. Records in the National Archives (and confirmed by the 1890 Veterans Census) show Otis volunteered in 1862 to serve in Company B of the Confederate Guards Regiment of the Louisiana State Militia fighting for the Confederacy. Why he traveled to Louisiana is a mystery.

Otis served under Captain George W. West and can be found in the muster rolls from March 8 to April 30, 1862. This unit was likely among the volunteer state militia that Louisiana Governor Thomas Moore transferred to Confederate Major General Mansfield Lovell for the defense of New Orleans.

Most of these men went into camps around the city for drill and discipline, according to Arthur Bergeron Jr., author of Guide to Louisiana Confederate Military Units, 1861-1865. New Orleans fell to the Union Army in April 1862. When Union General Benjamin F. Butler arrived, “the officers and men [in New Orleans] were arrested as prisoners of war, paroled, and those who did not take the oath, were exchanged,” noted Napier Bartlett’s Military Record of Louisiana.

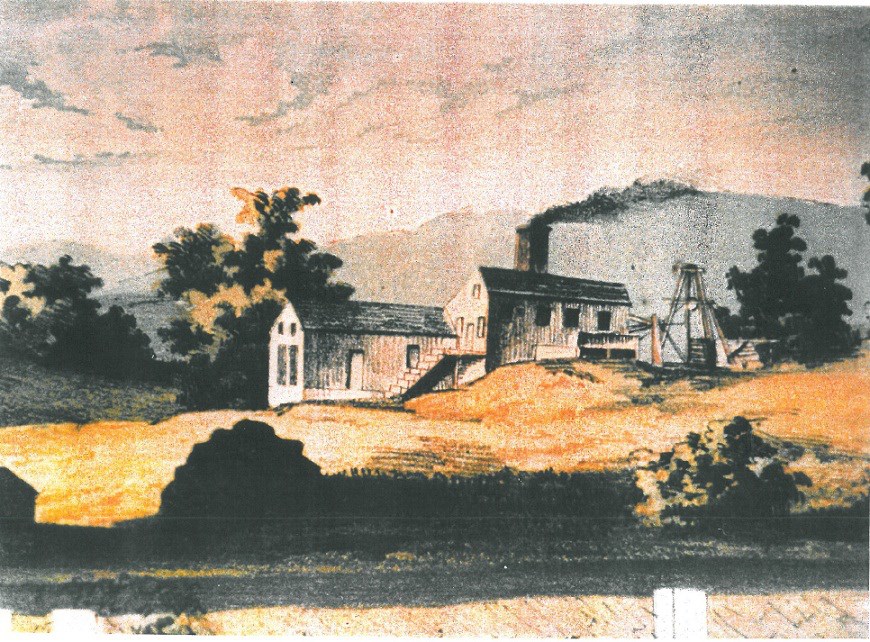

Otis eventually returned north. Tax records for 1865 and 1866 indicate he was living in NYC, but didn’t stay long. His wife’s uncle, John Moses, a retired New York businessman, had purchased the Case family farm. (Case had sold the property a few years earlier to individuals interested in copper mining; the mines were on the neighboring property now owned by St. Magdalen Church.)

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!