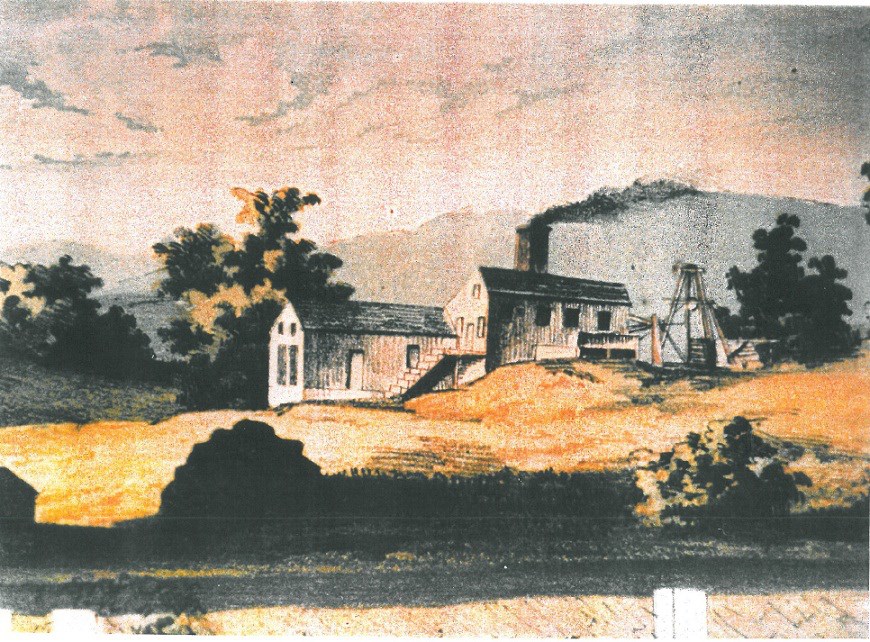

(Above photo): Rendition of the mining office located adjacent to the Case-Dvoor Farmstead.

The copper mining industry had been poking around Hunterdon County for many years in search of riches, when its interests zeroed in on the land we now call the Case-Dvoor Farmstead and the adjoining property on the east side of the Walnut (or Mine) Brook. This happened in the 1840s when workmen digging a cellar on the Capner Farm (on property once owned by Johan Philip Case) uncovered a surface vein of ore.

The Flemington Copper Company ignored a geologist’s advice against over-expansion, and hired a large crew of Irish miners, opened a number of experimental shafts and put in an anthracite smelter. A small collection of miners’ homes were built on what is now the Case-Dvoor Farmstead. (A recent archaeological dig here uncovered pipes, broken glass and other items believed to have belonged to the miners.)

Flemington Copper ran into a boatload of financial troubles, and sold its holdings to the Hunterdon Mining Company. Despite some early successes, this new company failed too. And, the company decided it had to drastically cut its workforce.

Up until the early months of 1861, a Captain Girardeau was in charge of the mines and lived quite handsomely in one of Flemington’s hotels. He was supposedly quite popular with the miners because he treated them fairly and drank beer with them. But in early 1861, he was replaced by a new captain, and as the Hunterdon Gazette reports, things quickly took a turn for the worst on April 3, 1861:

“The facts are these: — The week previous the company selected and sent on from New York to the mines, a new Captain, with instructions to pay off and discharge (with a few exceptions) all hands then and there employed. This was done, and the miners manifested their indignation, by riding the new Captain on a rail.”

(Interesting sidelight: Riding someone out of town on a rail was a literal thing, and it didn’t mean sticking someone on a train. According to tradition, the “rail” was either a fence rail or iron bar, and the subject of everyone’s ire was forced to straddle this rail while two men held each end. The person was then carried to the town’s border before being unceremoniously dumped.)

The captain reported to his bosses in New York. They sent him back on Tuesday, April 2, with a small force of hired hands to renew operations at the mines. The miners who been thrown out of employment gathered in front of the Union Hotel, and when the captain stepped from the stagecoach, greeted him with throaty cries and raised fists. Although great confusion prevailed for some time, no acts of violence were attempted, the Gazette reported.

The miners, after some 15 or 20 minutes of shouting, dispersed. About 8 p.m., the captain set out for the mines but was urged to turn back when about halfway there by those who had heard serious threats and feared he would be executed.

On Wednesday morning, accompanied by Sheriff Robert Thatcher, he tried again. As soon as the sheriff and captain were in sight, the miners “commenced riotous conduct again.” They cornered the sheriff and captain in the engine room. This small room was packed with angry miners and their even angrier wives, who appeared ready to tear the captain to pieces.

“Tar and feathers, we understand, (were ready), also an affair prepared upon which the Captain was to take a ride, as soon as he could be taken from the Sheriff,” the Hunterdon Gazette reported.

But neither the tar nor feathers nor rail were used. “The Sheriff stood his ground like a soldier and protected the Captain from violence, until assistance arrived from town, when there was a regular stampede of the Miners, and hot pursuit by the citizens for their arrest. The only injury the Captain received was the loss of a very good coat, which the women destroyed for him, the Gazette noted.

Thirteen miners were arrested and jailed for rioting. They were tried, convicted, and fined $20 a piece plus court costs. The Jerseyman publication noted that the purported ringleader, a Captain Hicks who was responsible for the outbreak, escaped arrest and punishment.

Newspapers more or less dropped writing about the Flemington Mining riot with good reason. Two days after the Hunterdon Gazette reported the outbreak, Confederate guns opened fire on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. The Civil War had begun.

(Sources for this article: The Hunterdon Gazette, April 10, 1861; Rural Hunterdon by Hubert G. Schmidt; The Case-Dvoor Farm Site Management Plan; and The Jerseyman, April 1891, “A Sketch of the Copper Mining Enterprise Near Flemington, New Jersey” by Elias Vosseller.)

Mine shaft covered by concrete off Shields Ave.