The Case Farm Tannery

On Nov. 11, 2018 our Farmers’ Market Second Sunday program series featured a presentation on tanneries and the 1803 murder in the farm house basement. In this blog post, we’ll tell you all about the tannery operating on the property. Next time, we’ll recount the events of the murder which occurred in the farmhouse basement.

The process of turning animal hides into leather goods was typically a home industry in the early 18th century in Hunterdon County. Farmers would construct vats and strip the bark from trees in the abundant woodlands to tan the hides of animals killed for meat. Some farmers quickly saw an opportunity to turn a profit by opening tanneries and accepting hides from area farmers. Among the earliest records of a tannery business in Hunterdon County dates to 1736 when two Quakertown farmers pooled their resources to purchase skins, pelts and hides; gather bark for tanning and to construct the pits, vats and mills for the tanning process.

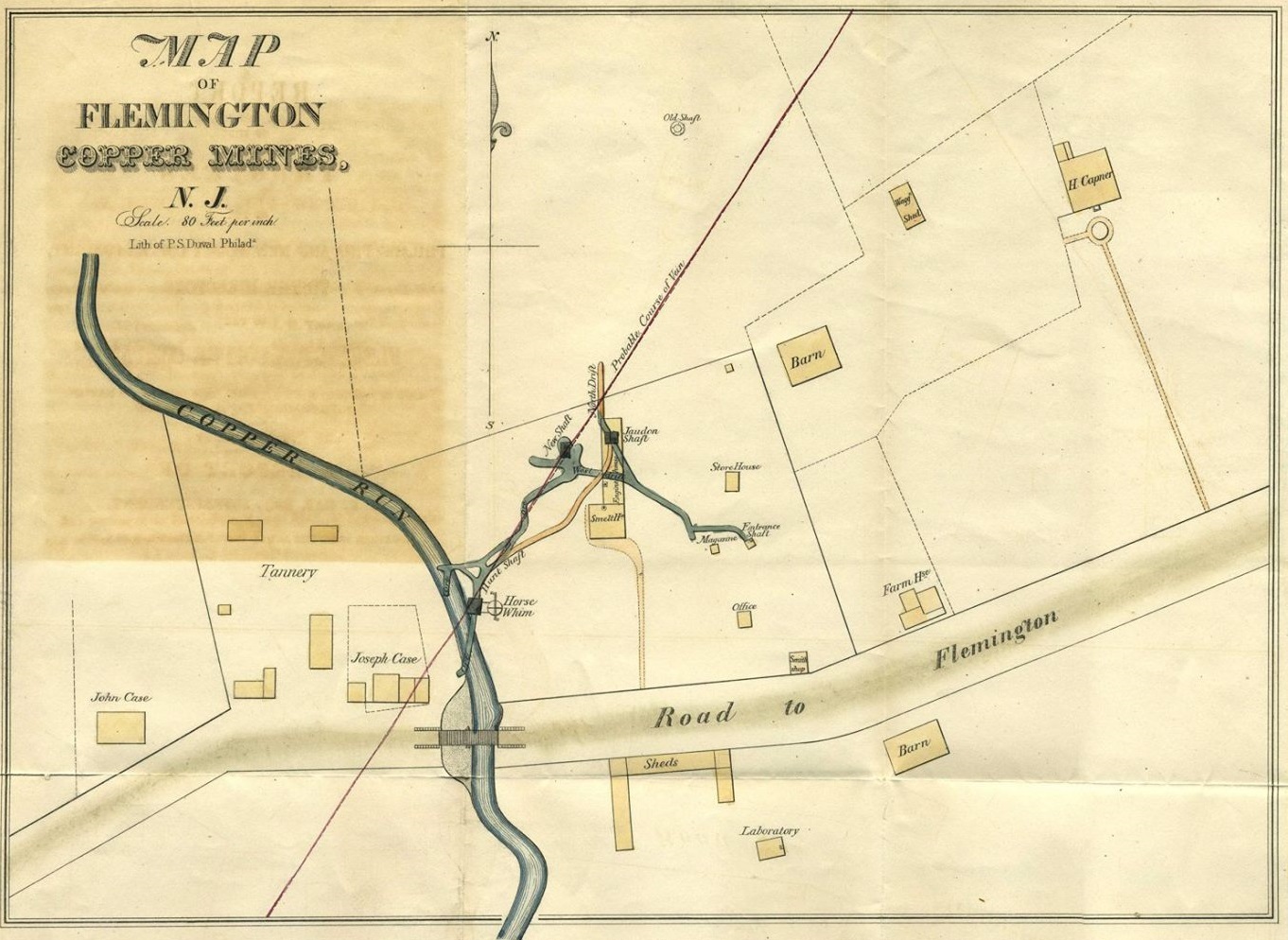

Philip and Peter Case — sons of Johan Philip, who was the first Case to settle in Hunterdon County — likely started their tannery around 1776. (Peter would sell his interest in the business almost a decade later.) The Cases had everything necessary to run a successful tannery: a water source on the property, an abundant supply of bark from the nearby woodlands, and a cheap supply of hides and skins. Tanneries were typically located near a town for convenience, but not within the city limits. The reason for that is, well, tanneries stunk to high heaven thanks to its putrid mix of decaying animal flesh, the pungent tanning vats and the pits with fermented manure that were part of the tanning process.

—

After the fall butchering season ended, farmers brought their hides — usually cattle, calves, horses, sheep and hogs — to a tanner like the Cases’. At times, the farmers delivered something a little less expected: In 1793, Jonathan Woolverton brought three skunk skins to the Case tannery.

The entire tanning process could take up to two years. Hides were first soaked in water for 30 hours before being transferred to a lime pit for up to a year. The lime would loosen dirt and animal hair. The hides were later moved to a bate pit containing fermented manure to remove the lime. This process, known as “drawing out the dung,” will come up again in part two of this blog when we discuss the details of the murder. The hides were then taken to a building known as a beam house, where any remaining animal hair was removed with a fleshing knife.

Once this task was completed the actual tanning process could begin. Hides were placed in a six-foot rectangular pit in the ground, about five-feet deep, filled with a tanning liquor made mostly from water and bark. The hides soaked for six to 15 months, and were moved daily to ensure an even tanning. A tanned hide was removed from a vat, drained and taken to a beam shed where it was beaten with a wooden hammer until smooth and supple.

Philip Case was also a currier. Currying was the process of taking leather and making it smooth and supple so it could be used for harnesses, gloves, binding books, etc.

When Philip died on May 5, 1831, the tannery passed on to his son, Joseph. But the business was beginning to die too. The 1840 census listed 23 tanneries in Hunterdon County. But those numbers steadily declined, and by 1860 there were only about seven tanneries operating in Hunterdon County. This drop resulted from both a diminishing supply of bark and hides, and competition from larger tanneries. It is believed the Case tannery closed around 1846.

During its 70 year history, the workers at the Case tannery never experienced a more traumatic day than on Oct. 7, 1803 when the farmhouse basement would become the site of a brutal murder. Stay tuned for part 2 coming soon!

Sources: Rural Hunterdon by Hubert Schmidt; Hunterdon County Tanneries by Phyllis D’Autrechy in the Hunterdon County Historical Society Newsletter, Fall 1989; Case-Dvoor Farm Historic Site Management Plan.